THE BATTLE OF MISSION RIDGE & BRIGADE HILL

Fixed, Flanked and .......

By Major Andrew Flanagan

The militia, having traded their lives for time, are sent back along the track towards Port Moresby, finally relieved by the AIF. The 2/14th and 2/16th fight a series of tactical withdrawals, holding the Japanese at suitable ambush sites. Those who have walked the track know these points – high ground, no room to manoeuvre, steep cliffs, killing zones. The Japanese are slowed, and held, buying time for the wounded to get back. The Australians know that any wounded captured by the Japanese will be murdered. The 2/14th and 2/16th are resupplied from Lake Myola, where air drops have built a stockpile of food, ammunition and medical supplies.

Although the Australians (militia and AIF) have caused significant casualties amongst the Japanese, the Australians have a problem – the next ‘defendable’ terrain is Mission Ridge/Brigade Hill, south of Lake Myola. The Australians, lacking artillery and heavy machine guns, need to choose defensive positions carefully – high ground, large enough to have three battalions (approx. 1000 men) dig in, where you can see the Japanese coming, and react when the Japanese manoeuvre to try and surround you. Ground where you can funnel the attacking Japanese onto the Australian guns, and wipe them out. Because if you don’t wipe them out, and if they do surround you, you’ll be fixed, flanked, and fucked! And, if that happens, the track to Moresby will be open. Grabbing everything that they can carry from Myola, the Australians withdraw to Mission Ridge, and wait for reinforcements.

Meanwhile, the 2/27th are sent ‘up the track’, having been held in reserve in case the Japanese launch an amphibious attack on Moresby, or defeat the Australian fighting at Milne Bay.

CPL Charlie McCallum, having miraculously survived at Isurava, staggers up the near-vertical slope from Efogi village to Mission Ridge/Brigade Hill. Sun beats down on his sweat-dripping slouch hat, he staggers under the weight of his weapon, ammunition, meagre food supplies, water and personal medical kit. Exhausted after nearly a month ‘on the track’, McCallum is heartened by the sight of the relatively fresh troops of the 2/27th. Alongside the survivors of the Battle of Isurava, McCallum waits for orders. Surveying the ground, good killing ground, the Australians are sick of withdrawing. Experienced veterans of the Middle East, and now the Battle of Isurava, these Australians are trained, and conditioned, to go on the offensive. Sitting in a weapons pit, fixed, unable to ‘get amongst the (insert enemy)’, the Australians are itching to turn things around. Brigade Hill is good ground to hold, but not for long given the wide-open valleys to the west towards Fagume River. Just long enough to get our breath, get more ammo, get the new blokes ready, get the wounded well back…then we do what we do best, get on the attack.

The Japanese rush reinforcements forward, scrambling after the Australians, knowing that to kill them in the open is much easier, much less costly, than if the Australians are allowed to concentrate their forces. Japanese officers catch sight of the Australians digging in on Mission Ridge, and urge the Japanese mountain-gun crews forward, bringing their artillery. Soon they will have six guns sighted on the narrow ridge, pouring fire from afar into the Australians, so close that they are unable to miss.

Brigadier Potts, commanding the Australians, has a decision to make: he is defending a narrow strip of land, terrain of his choosing, effectively blocking the track. To the east, he is protected by difficult high ground, hard for the Japanese to move large numbers of men to get at his flank. To the west, his flank is exposed somewhat but it’s extremely steep terrain. He has good observation of the approaching Japanese, and the capacity to call in air strikes – that is, IF the radio works, and IF there are aircraft to call in, and IF the weather is clear. Outgunned, he has no artillery, but some mortars. As a narrow ridge, he cannot really concentrate his men, they have to be strung out along the track. Given that the Australians are on a ridge, they will have limited water, and food and ammunition will have to be carried forward from HQ on the knoll at Brigade Hill. Wounded will need to either fight on, or be withdrawn through the Australian positions. Potts knows that Australian Army doctrine tells him to place (dug in) the weakened 2/14th and 2/16th on the exposed Mission Ridge – they number some 400 men, or 40% of their strength, and keep the fresh 2/27th (588 men) on Brigade Hill as a rapid reaction, counter-attacking force should the Japanese break through. This makes a lot of sense – dig your weakest troops in where they can fight in position, with your healthiest troops available to launch attacks where and when needed. Assessing the state of the survivors of Isurava, Potts does the exact opposite and orders the 2/27th forward, with the 2/24th and 2/16th strung out along Brigade Hill. Potts positions his HQ on a clear knoll to the rear, with D Company of the 2/16th as protection.

CAPTs Claude Nye and Bret Langridge are busy organising their men into positions along the ridge. Nye, aged 25, is a much respected veteran of the 2/14th. A Victorian, Nye had served with distinction in Syria. He orders his exhausted men to dig in, check ammunition, tend to scrapes and scratches. Nearby, Langridge, a West Australian of the 2/16th, does the same thing. Due to a childhood accident with a rifle, Langridge had lost the sight in one eye, and is affectionately known as ‘Lefty’. He had only passed the Army medical by memorising the eye chart. His fiancée is Miss Betty Dettman, a nurse serving with the 2/9th Australian General Hospital. Langridge commands D Company, positioned near Potts.

PTE Charles Dalling, aged 20, is a South Australian. Part of the 2/27th, he is busy digging in on Mission Ridge. Drenched in sweat, he gathers grenades and ammunition, sipping from his limited water supply. He can hear the Japanese across the valley, hauling forward their mountain guns. Dalling is too busy to be terrified – the ground is hard, and he only has his helmet to dig with. Surveying the scrape in the earth, a Japanese artillery round shrieks across the narrow valley. Dalling drops into his pit, the ground swallowing him to the waist. Ducking, the round thumps into the ridge, showering the men in clumps of clay. A near miss! Worn out, Dalling can dig no more…this will just have to do!

Japanese Colonel Masao Kusunose urges his men forward, eager to get at the Australians. So eager, in fact, that the Japanese are forced to struggle through the jungle at night, their soldiers carrying small pieces of captured Australian signal wire , lit at the tip. Sitting across the ridge, the Australians watch this ‘lantern parade’. Occasionally a light/soldier suddenly drops, slides and rolls, indicating a fallen Japanese soldier, a casualty of ‘the blood track’. Laughing, the Australians fire curses across the valley. Kusunose has 1,570 soldiers available. Although the Australians hold the high ground, Kusunose knows that there will be gaps in the Australian line. His plan is a simple one: attack the Australians on Mission Ridge, forcing them to push men forward in support. Fix the Australians with his mountain guns, get around the western flank, and cut them off. Once cut off, they can be killed in combat, or when they run out of ammunition, they will be killed in groups, by the bayonet.

The next day, September 6, Potts calls in an airstrike, killing two Japanese, and wounding two more. The following day, eight US B-26 and four Australian P-40 aircraft bomb and strafe the Japanese, killing a further eleven and wounding twenty. Heartened by finally having something to hit back with, the Australians enjoy the Japanese being on the receiving end of Australian firepower.

The Japanese launch their attack on September 7th, waves of screaming Japanese soldiers surging forward towards Mission Ridge under the protective fire of a barrage of artillery. The Australians, getting pounded on the ridge, open fire from their weapon pits, rolling grenades down on the Japanese. Twenty year-old Charles Dalling is fighting for his life – reloading his rifle as quickly as possible, he fires into the oncoming Japanese. Like a tsunami wave, the Japanese sweep in and around the Australian positions. Ferocious hand-to-hand fighting results, with Japanese and Australian soldiers intermixed. Men with agonising wounds fight on, many wounded multiple times, screaming in agony and rage. Dalling, rapidly running out of ammunition, fixes his bayonet, and fights on. With his mate beside him in their two-man weapons pit, they alternate reloading and firing, reloading and firing. The Japanese are held back, a momentary pause in the battle punctuated by a resumption in the Japanese artillery firing away. With little ammunition and almost no water, Dalling slumps down beside his mate, alive.

Back on Bridge Hill – Charlie McCallum, Claude Nye and Lefty Langridge listen to the sounds of battle, the clash of bayonets and screaming men easily carrying through the jungle. Brigadier Potts responds by sending crucial supplies of ammunition forward, along with water and medical dressings. The 2/27th have held the Japanese well, killing many, but have used up 6000 rounds of ammunition, and 1200 grenades.

The Japanese attack resumes, stopped only by the night.

With the Australians fixed in location, the Japanese 2nd Battalion creep through the night, following the Fagume River before cutting through the jungle towards the Australians. By chance, they cut the track between Pott’s HQ and the rear of the 2/16th, and commence digging in, unseen by the Australians. As dawn breaks through the jungle, Potts is fired on by the Japanese, narrowly avoiding being killed. With the bulk of the Australians forward and a Japanese battalion lodged on the track, Potts is facing a disaster, attacked from the front and rear! With only intermittent wireless contact, confusion breaks out. The 2/27th can hear gunfire to their rear, and assume the 2/14th and 2/16th are under attack. The 2/14th and 2/16th can hear gunfire to THEIR rear, and correctly assess that the Japanese have flanked their position and would soon be in a position to attack from the front and rear, wiping out the Australians. Through broken radio messages, Potts orders a company of the 2/27th to move back to the 2/16th position, freeing up a company of the 2/16th to support the 2/14th. In the confusion and fearing that they were being surrounded, the entire 2/27th withdrew through the jungle, leaving their dead behind. Mission Ridge had fallen, any wounded left behind massacred in their weapons pits by the Japanese.

With the situation rapidly unravelling, the Australians had only one option. As the relatively fresh 2/27th were cutting through the jungle and out of contact, Potts had no choice but to order the 2/14th and 2/16th to attack TOWARDS his position, and fast, in order to clear the Japanese from the track.

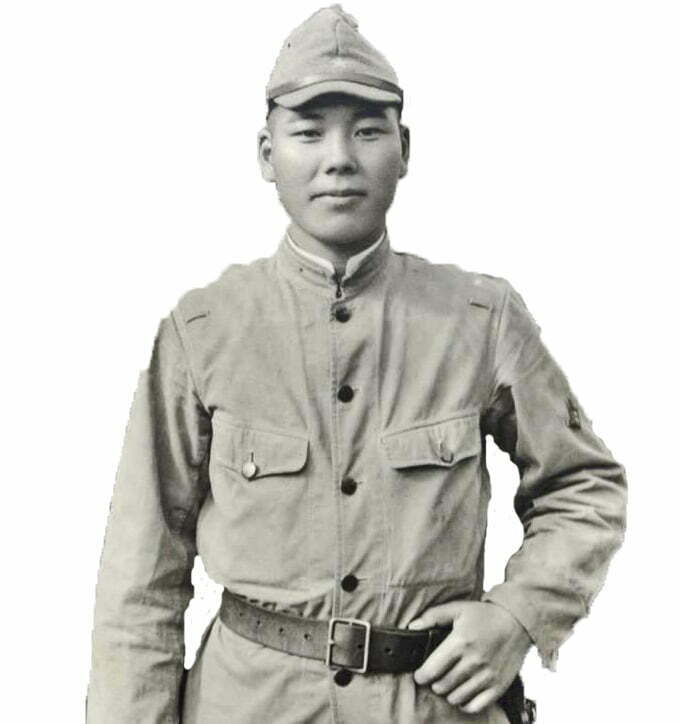

Japanese soldier Kokichi Nishimura is dug in between the Australians. Aged 23 and armed with a rifle and plenty of ammunition, he sits alone in his single-man weapons pit, surrounded by well dug-in Japanese, including a number of heavy machine guns.

Not far away, separated by thick jungle, the Australians issue orders for a quick attack.

In heavy rain, approximately 300 men of the 2/14th and 2/16th attack in a solid line. A number of Japanese positions are overrun, but the Australian casualties are frightening, cut down by a wall of Japanese machine gun fire. Japanese reinforcements rush forward as the Australian soldiers threaten to break through to relieve HQ. Nishimura is shot three times – he is the only member of his 56-man platoon to not be killed. He would survive the war, despite his wounds and further fighting on the northern beaches of Papua, including resorting to cannibalism as Japanese supplies ran out.

Charlie McCallum, nominated for a Victoria Cross at Isurava, is killed. CAPT Claude Nye is also killed, leading his men forward. Of the 300 Australians who participated in the attack, approximately eight broke through, the rest either killed, wounded or out of ammunition.

Potts, desperate now, orders D Company of the 2/16th to prepare to attack from his position, led by Lefty Langridge. Twenty-three year old Langridge, knowing that he was going to die, passes his personal items to a member of HQ, in the hope that they might be returned to his fiancée. Calmly, the Australians fix bayonets and advance towards the Japanese, where they are cut down. Langridge is among the men killed.

With two unsuccessful, costly attacks and darkness approaching, Potts has no choice but to order the Australians to withdraw, his HQ moving south along the track and the survivors of the 2/14th and 2/16th through the jungle towards the next defendable ground, Ioribaiwa Ridge. Defeated, the Australians would fight on at Ioribaiwa, the last ridge before Port Moresby, and if Moresby fell, Australia.

87 Australians and 60 Japanese were killed in the Battle of Mission Ridge and Brigade Hill.

Charles Dalling, aged 20, remains on Mission Ridge.

His body has never been located, the circumstances of his death unknown to his family back home. Did he die fighting beside his mate, perhaps killed instantly by a Japanese artillery round, a grenade or agonising gunshot wound? Did he somehow survive the battle, before being bayoneted by a Japanese soldier? Did he die, alone in the jungle, thinking of his family back home in Australia?