THE BATTLE OF ISURAVA

Holding on for the AIF, standing side by side.

By Major Andrew Flanagan

Battered, the 39th Battalion withdraw to the next ‘defendable ground’, a collection of small, open spaces of relatively flat ground at Isurava, three or four tennis court-sized killing zones perched on the side of the Kokoda Track. They are horribly exposed on one side of the valley (imagine a wishbone), with their right flank defended by their fellow militia of the 53rd Battalion. If one fell to the Japanese, the other would be cut off and destroyed. If either fell, the path to Moresby would be wide open. Advancing ‘up the track’ are the experienced warriors of the AIF, strung out on a single-file mountainous path. If the ‘chocos’ at Isurava can’t hold, the ‘deep thinkers’ of the AIF will be wiped out as well. They are all that stands between the Japanese and Moresby.

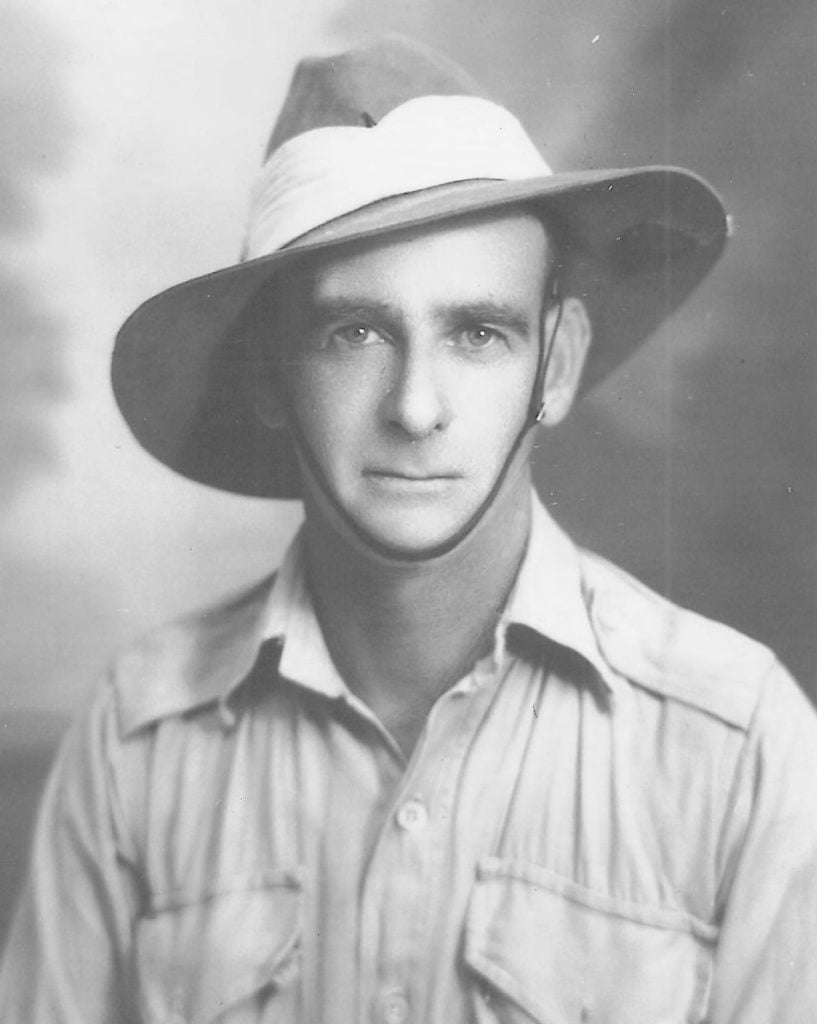

Between the AIF and the 39th Battalion at Isurava is LTCOL Ralph Honner, slipping and sliding along the muddy track to Isurava. He has been sent to command the 39th Battalion, and he is prepared to die to hold the Japanese. Born on 17 August 1904, he is an intelligent, thoughtful father and school teacher. He had commanded the 2/11th Battalion in the Middle East, including the disastrous withdrawal from Greece and defeat on Crete. In short, he had experienced much in life and was the perfect man to lead the shaken militia at Isurava. He knew the importance of adopting an offensive spirit, building morale, and, most of all, creating hope amidst a seemingly hopeless situation. He arrives at Isurava at midday, 17 August 1942 – his birthday.

With the arrival of LTCOL Honner, suddenly the Australian militia of the 39th and 53rd Battalions have hope! He is briefed by MAJ Cameron, who informs him that in his opinion B Company of the 39th are not fit to fight, and should be broken up and mixed in with the other companies. MAJ Cameron believes that the men of B Company lack courage, and will not hold out against the Japanese. LTCOL Honner walks the ground at Isurava – the high ground on his left flank, in places vertical, the men digging in here likely to be cut off. From the left flank, the ground tumbling down to the track, pausing on a perch of flat ground before resuming a near-vertical drop to Eora Creek, before sweeping up again to the 53rd Battalion far away across the valley. Honner anticipates that the Japanese will attack from the high ground, concentrating their men in overwhelming numbers. The Japanese plan will be simple – hammer the Australians with their mountain guns, sweeping the ground with their heavy machineguns followed by waves of Japanese soldiers. Overrun the Australians on the high ground, using the momentum of the mountain slope to descend on the main defensive position, killing all in their way. Get in amongst the Australian position, like a tsunami, unstoppable. For both the Japanese and Australians, the high ground on the left flank would be decisive. It is the key to Isurava, and for the Australians must be held at all costs. Honner knows that he needs every man in the fight, including B Company. He is outnumbered, and out gunned. The Japanese have mountain guns and heavy machineguns, he has none. The Japanese can choose their assault and concentrate their attack on a small area, the Australians are fixed in muddy weapons pits, and must defend the entire perimeter. They are a thin khaki line, hoping to hold on until the AIF arrive, but preparing to be killed in order to trade their lives for time. They assume that if they don’t hold, the Japanese take Moresby, and if Moresby is in Japanese hands, Australia falls.

Honner walks amongst the men, quietly instilling calm and confidence. He refuses to break up B Company – in fact, he places them on the high ground, the ‘post of honour’ on the left flank, where the Japanese will surely attack. He explains the reality of the situation; the Japanese will pound you will everything that they have, you will be outnumbered 10 to 1, the Japanese will throw wave upon wave of men at you, and you will feel very, very alone. But, you will not be alone, because we will do everything that we can to keep you alive. At times, you will be low on ammunition, but we will scale this mountain and bring you what you need. At times, your positions will be overrun. But, you are not alone, we will counter-attack with everything that we have, and we will come for you. You must hold, and you will hold! Because if you do not hold, then we will all die. But, we will die here together. There will be no withdrawal until the AIF get here. Australia depends on you. I need you to hold the ground, and you WILL hold the ground. You will.

Slowly, the men come to believe. A belief in themselves as soldiers, in the man beside them, in each other. If this quiet, unassuming, experienced LTCOL believes in us, then by god, we won’t let him down! If it takes the AIF a day to get here, then we will hold for a day. If it takes a week, no worries mate, we’ll hold for a week. Longer? No worries, she’ll be right. 400 Australians up against 3500 Japanese. No problem, we’ll give as good as we take, and more. We’ll hold…

Quietly, the men resume digging with their helmets and bayonets, laying out magazines and grenades. Meanwhile, the Japanese move their mountain guns onto the high ground, watching the Australians exposed and digging in. Japanese soldiers, with fixed bayonets and heavily camouflaged, creep silently through the jungle, approaching the Australian left flank.

Around midday on the 26th August, the Japanese attack begins. Just as anticipated by LTCOL Honner, B Company on the left flank are hammered by artillery, and pinned in position. The Japanese burst from the jungle in a wild frontal attack, in amongst the Australian positions. Throwing themselves into the Australian weapons pits, the battle disintegrates into a series of isolated, one-on-one fights to the death. To the left, an Australian soldier is impaled on a Japanese bayonet, screaming for his mother as he dies an agonising death. His mate beside him swings his rifle around, frantically firing a shot at close range. Missing, he reverses the rifle and clubs the Japanese soldier to death, too slow to save his mate. He resumes firing into the wave of Japanese troops charging through the position. Further to the right, an Australian and Japanese soldier roll around in the jungle mud, clawing at each other’s throat, until both are killed by a grenade rolled from an unseen Japanese soldier crouching in the jungle. Another Australian, out of ammunition, drags his wounded mate to the rear of their position, grabs more ammunition and returns to resume the fight. Just as the Japanese seem certain to overrun the Australians, they are stopped, their wounded melting away into the jungle.

LTCOL Honner, on the flat ground below the left flank, sends ammunition and medics up the hill. B Company have held the first attack, but have used a lot of ammunition, and suffered many dead and wounded. Honner has no reserve, no more men to send. The other companies of the 39th, dug in themselves, wonder if B Company will hold on.

The Japanese rush new men forward, launching attack after attack on the rapidly dwindling men of B Company. Further Japanese troops probe around behind the Australian positions, threatening to cut of the 39th Battalion. Suddenly, the entire position seems to be under assault. Meanwhile, the Japanese 3/144th Battalion attack the Australian right flank across the valley on the Abuari ridgeline, held by the untried 53rd militia battalion. Engaged everywhere, the Australians have no option but to fight to the death, waiting for the AIF as their only chance of reinforcement. On the Australian left, B Company is overrun in places, wounded men fighting on, seemingly alone. The Australians counter attack, driving the Japanese out. Japanese machineguns tear through the Australians, any man above his weapons pit killed. But they have held, and will go on holding. The AIF are on the way, one company at a time, and due to arrive at any minute. The battle rages, the ‘crack’ and ‘thump’ of Japanese artillery signalling further death and destruction. The ground shakes, as though pounded by a giant. Australian and Japanese blood spurts out of wounded and dying men, soaking into the ground as one. Exhausted, the Japanese attack splutters, stumbles, and stops. The forward companies of the AIF – 2/14th and 2/16th – arrive mid-afternoon, dropping into the Australian weapons pits alongside the gasping men of the militia, many of whom are wounded, but fighting on.

Morning, 27 August, finds the Australians fighting side by side as the Japanese resume their attacks, both on the high ground and probing the flanks and rear of the Australian position. Further attacks on the Abuari ridge threaten to overrun the 53rd Battalion and 2/16th, which would result in the 39th and 2/14th being surrounded. As the AIF arrive in strength, the militia are withdrawn to form a reserve. For B Company on the left flank, they have held their ground, despite numerous attacks. They have sacrificed much, most are wounded, many are killed. But they held, because LTCOL Honner said they would, and because their mates were relying on them. Those who survived entered the battle as boys, and came out seemingly as exhausted, old men. But they held!

Assuming the defence of Isurava, the 2/14th perimeter gradually shrinks as the Japanese rush in fresh troops. Running low on ammunition and men, the Australians on the high ground are ordered to withdraw. CPL Charlie McCallum, aged 35, stands his ground. He orders his men to pull back to safety, standing with a Bren light machine gun in one hand and a Thompson sub-machine gun in the other. As the Japanese close in on his position, he mows them down, buying valuable minutes for his men. Japanese soldiers rush him, getting close enough to grab his ammunition pouches, before he cuts them down in a hail of bullets. Calmly, seeing that his men are safe (for now) Charlie McCallum gives up the position and rejoins his men.

Assuming the defence of Isurava, the 2/14th perimeter gradually shrinks as the Japanese rush in fresh troops. Running low on ammunition and men, the Australians on the high ground are ordered to withdraw. CPL Charlie McCallum, aged 35, stands his ground. He orders his men to pull back to safety, standing with a Bren light machine gun in one hand and a Thompson sub-machine gun in the other. As the Japanese close in on his position, he mows them down, buying valuable minutes for his men. Japanese soldiers rush him, getting close enough to grab his ammunition pouches, before he cuts them down in a hail of bullets. Calmly, seeing that his men are safe (for now) Charlie McCallum gives up the position and rejoins his men.

The Japanese sweep down the right flank, pushing the Australians back and threatening to cut off the Australian headquarters. The situation is perilous, the Japanese close to victory. The Australians must counter-attack and wipe out the Japanese, or risk being annihilated. 24 year-old PTE Bruce Steel Kingsbury is one of only a few survivors of his platoon, however he volunteers to join the attack. With him is CPL Lindsay Bear, who is armed with a Bren gun. The Australians rush forward, Bear firing from the hip. Hit in the face and wounded twice in the leg, Bear hands his Bren to Kingsbury, who charges forward, wiping out countless Japanese soldiers. The surviving Japanese flee into the jungle. Kingsbury, pausing to reload, is shot in the head, killed instantly. His devotion to duty, personal sacrifice and inspiration had saved the position. PTE Kingsbury is awarded the Victoria Cross. He lies forevermore at Bomana War Cemetery, Port Moresby.

CPL Lindsay Bear, unable to walk, lays beside his mate Russ Fairburn, who has a Japanese bullet lodged near his spine. Surrounded by badly wounded, the two refuse to be carried out by stretcher. They commence crawling along the track……

30 August finds LT ‘Butch’ Bisset fighting for his life. He is one of 35 men, under attack by waves of 100+ Japanese soldiers. The Japanese would attack his position 11 times throughout the day, each time failing to wipe out the determined Australians. Butch is 32 years old, and much loved by his men. His beloved brother, Stan, is also at Isurava, part of the headquarters. Butch, despite being under heavy fire, crawls through his position, keeping his men supplied with grenades. A burst of Japanese machinegun fire stitches him across his stomach, an agonising wound. Grasping his stomach, blood seeping through his fingers, Butch draws his pistol as his men frantically try to get to him. Butch orders them to leave him rather than risk their lives trying to save him – they refuse, and a number are wounded as they drag Butch from the battlefield. Taken back to the Regimental Aid Post on a stretcher, Butch loses consciousness. Men rush to find Stan, knowing that a stomach wound is fatal. Stan joins Butch, laying in the mud alongside his stretcher, surrounded by the sounds of battle. Butch, as though sensing that his brother is there with him, regains consciousness. He is given morphine to relieve the pain. As night falls, Butch falls in and out of consciousness. Throughout the next six hours, Stan remains by his side; holding his hand, as they talk about their childhoods, precious memories. At 4am, Butch dies.

Stan, and Butch’s men, are heartbroken.

CPL John Metson is 24 years old. Shot through the ankle, he is unable to walk, and finds himself with a group of Australians cut off and surrounded by the Japanese. Forced to leave the track, the group have no choice but to try and cut through the jungle, avoiding the Japanese. Despite being unable to walk, Metson refuses to be carried on a stretcher, as ‘there are men worse off than me’. Wrapping his knees and hands in a blanket for padding, he craws through the jungle following the rest of the group, including those men on stretchers. Unable to keep up, Metson falls behind. As the group rests at night, Metson crawls after them, silent in his agony, his determination an inspiration to all. He crawls after the group for three weeks as they meander through the jungle, avoiding Japanese patrols. Low on food and with the wounded become weaker by the day, the group rest at Sangai village. CPL Tom Fletcher volunteers to stay and look after the wounded, including Metson, while the rest of the group attempt to get help.

A Japanese patrol discovers the wounded at Sangai, and murders them all, including Metson and Fletcher.

The militia (39th and 53rd) and AIF (2/14th and 2/16th) have held the Japanese at Isurava. In a relentless, vicious battle lasting four days, 99 Australians lie dead on the battlefield, with 111 wounded, many a number of times. The Japanese have lost 140 killed, with 231 wounded. Among the Australian dead are Butch Bisset and Bruce Kingsbury. Lindsay Bear, Russ Fairburn and John Metson leave the battle crawling through the jungle. Bear and Fairburn would survive, amazingly. Also amazing is the fact that Charlie McCallum has survived, given his fight on the high ground. Withdrawing from Isurava with his men, McCallum is determined to fight on. With him is the devastated Stan Bisset, forced to leave his brother behind, buried alongside the track.

The people of Isurava village would relocate their huts after the fighting passed, believing the ground possessed by spirits – unnerved by the nearby river turning red with the blood of the fallen.